“But what do we really know, finally, about this woman of the Middle Ages, who dared to wear men’s clothing, mounted a horse, made war, who addressed her words to the greatest lords of her time with such ease that her attitude approached insolence, who showed her judges an extraordinary effrontery?” (Marcel Gay, Roger Senzig, “L’Affaire Jeanne d’Arc”)

Indeed: what do we really know about her? One used to say – and this is already almost a truism – that Joan of Arc is one of the best documented personalities of the European Middle Ages. And indeed, if to measure it by the mere number of archival documents – not to mention the size of some of them – this truism is absolutely correct. On the other hand, many of these documents are divergent or even directly conflicting as to the information contained therein. As a matter of fact we know for sure that in general she existed and played an active role in the Hundred Years ‘ War, contributing in some way to the turning of the scale of victory to the advantage of one of the warring parties. A lot is based more on conjecture than on anything proven.

Was she indeed someone leading an army to battle, or did she hold the function of a leader only formally, while remaining more a kind of “figure-head” and “mascot”? Ongoing disputes about it know virtually no end. Was she a military leader more in the “technical” sense, or rather a kind of a “political commissioner” who cared about ideological cohesion of the army? The term “political commissioner” or “political officer” in a country ruled by communists might be wrongly understood. But let us remember that it was not the communists who came up with this concept, because it had been used previously and was first used – nomen omen – as Joan of Arc, in France at the end of the 18th century (“commisaire politique”).

Did she show leadership, changing the course of events, or was she merely used by someone else and taken advantage of and then was disposed of unceremoniously when her usefulness greatly decreased? Or perhaps someone was trying to take advantage of her but her speedy career and popularity began finally to threaten someone? To this day, for example, the dispute has not been settled about whether she was captured accidentally or through treachery and a trap deliberately set …

As a matter of fact we can not prove in any way even those seemingly most basic facts of her life, like her date of birth, age, place of birth, social background and education. Nobody is able to demonstrate whether she indeed died at the Inquisitorial stake. Because if on one hand the full manuscripts of the minutes of her condemnation trial have been preserved (and namely in quite a few copies!), then on the other hand not only do we not have the minutes of her execution, but in addition we do not even know about anyone who at any time, whether at present or in the past, ever having argued that he had seen them with his own eyes.

And the question of her “inspiration” by the divine, of course, cannot even be subjected to any empirical reasoning because it lies totally outside anything empirical.

Therefore, Jeanne will remain a mystery for a long time, and the participants in the debate on her can be sure only of one thing: of what they personally believe and what they want to believe.

Imperfect historiography

Of course, one of the reasons for this state of affairs is that the scope for a historian used to be much narrower in the past than it is now. A historian could rely only on what he read as written by other authors or on what he personally heard. Archaeology, which, starting from the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, often placed a lot of clichéd and “proven” “facts” from the past “upside down”, was yet unknown. Unknown was the “carbon dating” of artifacts and human remains. There was no notion of the existence of DNA. There was no archival footage or photos (what would we say to a “souvenir photo” of Jeanne and Jean de Dunois in front of the gate of the just taken “Tourelles” in Orleans or photograph of the fallen William Glasdale?). As aviation also did not exist, there could be no way of recognizing the erstwhile buildings from the air, which is now possible even if there seems to be no visible trace of their former foundations.

The only thing, therefore, that we are left with, is to inquire into the probability of who Jeanne was and what she could have been like. And in this case, we know that to some people some things are more likely than to others. Which of course should rather lead to careful formulation of hypotheses, rather than attempts to impose “dogmatic” opinions in an overbearing (and often outright insulting) way as if one was an infallible “Alpha and Omega” entitled to contemptuous (and even openly hostile) attitudes towards people whose only “fault” is to have a different opinion… And we can consider ourselves lucky, that in the case of the story of Joan of Arc no Revisionist is going to go to jail for a couple of years for “unorthodox” or “illegal” views. Indeed, such barbaric abuse of law has been in our time reserved to “assist” interpretations of some other, much later events of so-called “Modern History”, especially WW2…

Painstaking search for Joan

In relation to Jeanne – no matter what her origin was (peasant or Royal) and what her leadership role was based on, it is most likely that she was extremely “tough”. The records of her trial in Rouen alone would strongly suggest that. But any person who for any reason goes to war and takes part in battle, is repeatedly wounded without however giving up the fight, and enjoys popularity among the army, must virtually be firm and free from much hesitation. Perhaps she was not necessarily the type who you would describe as “ihr Blick war stählern” (“her eyes were steely”), though … let us not anticipate events.

The issue of Jeanne’s appearance has already been addressed twice in previous parts. But it has been done only partially, not completely. Here we will supplement previous information, the more so that a person’s appearance is not limited only to facial traits. Her appearance, moreover, is to a certain extent associated with certain skills possessed by Jeanne, and her skills are also a subject of this text.

We do not have any image of Joan of Arc which is known as her faithful portrait. Although it is known that during her life at least one portrait of her was painted. On Saturday March 3, 1431, during interrogation, Jeanne was asked whether she had ever seen or commissioned any portraits or images of herself, she replied that “she saw in Arras a picture in the hands of a Scotsman and it resembled her, showing her in her full armor and handing a letter to her King, while kneeling on one knee. And she had neither seen nor commissioned any other image of herself “. (p. 66)

There is a conjecture that this portrait was made by the Scottish painter Hamish Power (also known as Hauves Poulnoir) residing in Tours. He was also the author of Jeanne’s two banners ordered by the King, for which he received “25 Livres tournois ”. What strikes us, however is the fact that Jeanne saw the portrait in Arras in the summer of 1430, a number of weeks after she had been captured. The Scotsman was allowed to visit the captured Jeanne in the residence of the Duke of Burgundy in the heart of the city to show her the portrait. This example is one of many which show the changing conditions of treatment of her as a prisoner.

We know nothing more about the portrait itself (so far at least…).

However, there are descriptions of the appearance of Joan of Arc. We have already mentioned, and namely twice, the dubious “letter” by Perceval de Boulainvilliers (the original of which has never been found, but only copies) to the late Duke of Milan (who had died 17 years earlier!). The “letter” also contains the following description:

“This Maid is appropriately graceful, has virile bearing, and in conversation shows great common sense. Her voice has a feminine charm; she eats little, limits herself in drinking wine. She loves beautiful horses and armor, and is very fond of armed men and noblemen; she avoids big and high-profile meetings, often sheds tears, her face is joyous. She has incredible strength and resistance to fatigue and wearing armor that she can hold out for six days and nights without removing even one part of the armor.”

( “Haec Puella competentis est elegantiæ, virilem sibi vindicat gestum, paucum loquitur, miram prudentiam demonstrat in dictis et dicendis. Vocem mulieris ad instar habet gracilem, parce comedit, parcius vinum sumit ; in equo et armorum pulchritudine complacet, armatos viros et nobiles multum diligit, frequentiam et collocutionem multorum fastidit, abundantia lacrimarum manat, hilarem gerit vultum, inaudibilis laboris et in armorum portatione et sustentatione adeo fortis, ut per sex dies die noctuque indesinenter et complete maneat armata”.)

Charles’ VII Fiscal Prosecutor, Mathieu Thomassin, described her so: “she was dressed like a man, she had short hair and a woolen cap on her head and wore simple linen shirts like men”

Guillaume Cousinot de Montreuil (1400-1484) in the “Chronique du Pucelle” wrote:

“She was 17 or 18 years old, with good proportions of the body and strong”. The author adds that having arrived in Vaucouleurs to captain Robert de Baudricourt she “… seemed to him that she may be in the right place among those people and prevented fights, and some wanted to try fight among themselves, but when they only saw her, they froze and lost their will” (“…ils étaient refroidis et ne leur en prenait volonté”)

We would give a lot to find out what exactly so “chilled” these feuding warriors in Vaucouleurs. Could it be indeed that “ihr Blick war stählern” after all, all the more so if she was to have had blue eyes? Marcel Gay and Roger Senzig believe (“L’Affaire Jeanne d’Arc”), that this quote from “Chronique” proves Jeanne’s “intimidating appearance” (“physique intimidant”). But perhaps they “froze” as a result of the simple fact that they noticed that this young woman, dressed and presenting herself as they did, was however able to behave much wiser.

In another literary work “De cleris mulieribus” (“On famous women”) its author, Jacques Philippe Foresti de Bergame, seems to cite someone else’s earlier observations (because he himself lived between the years 1434-1520):

“She was of short stature with a face of a peasant and black hair, but each of her limbs was strong.”

We would give a lot to know what he understood as a “face of a peasant “: whether he meant features or just having a tan, which was regarded as being “peasant-like” among women…

Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti (1445-1510), also previously quoted:

“She is beautiful, with the face a bit sunburnt and crowned with blond hair.” (in: “Ginevera de la Clara Donne”).

Arienti did not know Joan, hence the “blond hair” in his text. It just so happens that every person who knew Jeanne described her as having black or at least dark hair. But in the iconography she is often – if not mostly – presented indeed with blond or red hair. Anyway, a variety of hair color was often used in icons to differentiate between “good” and “evil”. For example, frequently the fight between the Archangel Michael and Lucifer is portrayed in icons as a fight between the fair-haired and fair-skinned (and sometimes also blue-eyed!) “Michael” with the darkish and black-haired “Lucifer”.

I recall an exchange of opinions (on the Internet) with a fairly prominent American White Nationalist who also is of the opinion that the hair of Joan was either blond or red. His opinion is based on a medieval miniature dated with the years 1455-1485, and which is therefore of the period in which there could still have been living in France people who personally remembered Jeanne. He wrote then on his website, citing our “conversation”:

I recall an exchange of opinions (on the Internet) with a fairly prominent American White Nationalist who also is of the opinion that the hair of Joan was either blond or red. His opinion is based on a medieval miniature dated with the years 1455-1485, and which is therefore of the period in which there could still have been living in France people who personally remembered Jeanne. He wrote then on his website, citing our “conversation”:

“The earliest painting of her, in COLOR of course, the one shown above from 64 years after her judicial murder, shows her as a redhead, and she was a very, very famous woman, seen by THOUSANDS. She was, let’s face it, the equivalent today of a rock star! Furthermore, France is or once WAS fundamentally keltic and often red-headed. (Hans F. K. Günther wrote in his “Racial Life of the Indo-European Peoples” that a study of recruits in Napoleon’s army in the year 1800 showed 70% had BLUE EYES, reflecting the original French look before the wars of Napoleon and WWI decimated the true French stock). The French are basically a keltic-germanic-mediterranean mixture. The northeastern province of Lorraine, next to Alsace, then in Germany, specifically was heavily keltic-germanic. ”

http://www.democratic-republicans.us/english/english-happy-birthday-today-in-1412-joan-of-arc

He was glad, therefore, when I presented him with the reconstruction of the face of Jeanne developed in the Bundeskriminalamt in Wiesbaden (Germany). He saw in this reconstruction a confirmation of his own opinion.

He was glad, therefore, when I presented him with the reconstruction of the face of Jeanne developed in the Bundeskriminalamt in Wiesbaden (Germany). He saw in this reconstruction a confirmation of his own opinion.

But the authors of the reconstruction (mainly Professor Ursula Wittwer-Backofen) did not take into account the preserved medieval written descriptions of the appearance of Jeanne, but one sculpture with the alleged face of Joan and the facial profile of Jeanne des Armoises. It’s true that both physiognomies have bright eyes (in the case of Jeanne des Armoises they are clearly blue). But blue eyes are not only “the domain” of blondes. In addition this profile of Jeanne des Armoises clearly has raven black hair.

As if that wasn’t enough, there have survived to modern times (though not to our times, unfortunately,) two hairs, probably of Joan, squeezed in the seals of letters sent by her. One of these letters is a letter to the people of Riom from November 9, 1429. The second letter is the one presented here on another occasion, written on March 16, 1430 to the inhabitants of Reims. The first letter was “discovered” in the archives of Riom in 1884 and described, together with the stamp, by Jules Quicherat. There existed in the Middle Ages a custom, fairly often adhered to, of pressing a hair into the still soft and hot seal of a letter. This custom was used to confirm the authenticity of the wax seal. The seal of the letter from the year 1429 still exists, even with the thumbprint. But the hair has already been lost many years ago (already in 1936, Vita Sackville-West reported its disappearance in her famous biography of Joan). From the letter from 1430 the hair disappeared, however, together with the stamp.

Jehan Bréhal adds more details to the description of Jeanne. Bréhal was the high ranking cleric with the official title of the Grand Inquisitor of the Faith in the Kingdom of France. It was Bréhal who later presided over the rehabilitation trial of Jeanne in 1456/57. Here’s what he claimed:

“She has a red spot on the skin behind her right ear. Secondly, she speaks softly and clearly, and thirdly she has a short neck.“

We have based our own attempt to reconstruct the profile of Jeanne d’Arc on the facial profile of Jeanne des Armoises from the Jaulny Castle. In the first place, therefore, in view of the fact that the portrait depicts a woman around her middle age, we have attempted a “rejuvenation” of her face and we have removed the woman’s headgear. Then we’ve duplicated a typical medieval “hairstyle” characteristic of the feudal nobility, keeping in mind the preserved remarks about the “short-haired” Jeanne. As a comparison we present here some similar Medieval hairstyles, the examples being of the Duke of Burgundy, Philippe Le Bon, and the English King Henry V.

And then we have placed a replica of a medieval helmet and armor onto the profile. Jeanne was probably donning a variety of helmets, but most likely she used, as Adrien Harmand suggests (“Jeanne d’Arc. Ses costumes, son armure: Essai de reconstitution “, Paris, 1929), the type of helmet called a “sallet” without a visor. We present her here in just such a helmet.

However, there is no shortage of opinion that she was using different types of helmets. One of them is this helmet, known as a “bascinet” (or “bassinet “), which is considered by some to be the authentic helmet of Joan, preserved in Orléans at the Church of St. Pierre le Martroi where it hung over the main altar.

As you can see, there is even a piece of string on which it hung. This helmet certainly had a visor because both sides still have its hinges. How such helmets look with visors can be seen on these two photos.

Clearly, our reconstructions of the facial profile should be treated only as a kind of guess as to how the face of Joan of Arc could have looked. Our studies of her face as well as attire are only in their initial stages and will be continued. We will continue to publish the results obtained. The full set of images created so far is available on our Facebook. And in future we’re going to recreate the whole portrait of Joan with her attire in full colour.

Of course, suits of armor were not the only “attire” of Jeanne. Documents reveal that a lot was also sewn for her, sometimes of expensive fabrics. Here are a few examples of what she used to wear.

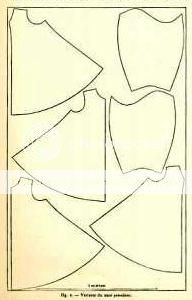

These three illustrations come from a 400-page work by Adrien Harmand which was mentioned above. As for the two garments shown on the right, we remind the Reader that these are men’s clothing, though today they do not make such an impression. In this way the French aristocrats, Princes and Kings dressed in the 15th century.

The costume to the left – which was supposed to be all black – was the one in which Jeanne travelled from Vaucouleurs to the residence of Charles VII at Chinon in the beginning of her mission. It is possible that she was dressed similarly during her first journey from Vaucouleurs to Prince Charles II of Lorraine, who specially invited her to his residence in Nancy. Both Nancy and Chinon will be mentioned later in the text, in view of the skills demonstrated there by Joan. This costume also became circumstantial evidence in the assumption that Jeanne was a member of the Third Franciscan Order, which we mention later, in part 6 of our series, namely in the section Was Joan a Tertiary?

And the costume similar to the first on the right, on the other hand, served Harmand to determine Jeanne’s height:

“ These different parts are to be arranged that they lay placed in accordance with the threads of the fabric, in order to avoid unnecessary loss of valuable fabric by the tailor Jean Bourgeois on two ells of fine Brussels, provided by the clothier Luillier, before applying scissors.

“ These different parts are to be arranged that they lay placed in accordance with the threads of the fabric, in order to avoid unnecessary loss of valuable fabric by the tailor Jean Bourgeois on two ells of fine Brussels, provided by the clothier Luillier, before applying scissors.

It can be seen, from the scale of the accompanying image, that the fronts of the dress in question measure eighty-five centimeters, from the neck to the lower edge (…). Knowing that men’s dresses were reaching knees, we must conclude that a man dress, cut in two ells of cloth , could only fit a person measuring eighty-five centimeters from the base of the neck to the kneecaps. However, this feature is only found among those normally shaped women whose height exceeds one meter and fifty-seven but does not exceed one meter fifty-nine centimeters. As a result, Joan of Arc, well built and with strong limbs, beautiful and well-formed , would reach approximately one meter and fifty-eight, since the length of her dress of fine Brussels measured eighty-five centimeters.” (“Jeanne d’Arc. Ses costumes, son armure “, 1929, pp. 312-313)

The first known visual representation of Jeanne, in the form of a cartoon from Paris, depicts her as from the military: with a sword and banner.

Since then she has been portrayed in iconography with a sword and banner on monuments, sculptures, paintings, stained glass, as in this example from Perth in Australia . It is true that in battle she often held the banner herself (and one of her contemporaries even made a remark during her rehabilitation trial that she was more willing to hold her banner rather than her sword …), but it was mostly carried by someone else, namely her page. Here we see a 15th-century tapestry made in Germany, and showing Jeanne meeting King Charles VII. We will put aside the “typically medieval” proportions appearing in the tapestry or even the wrong colour of the banner. After all, the tapestry was not made in France and the authors most likely did not meet Jeanne personally. But what these people certainly knew was the fact that a knight usually did not carry his banner, but his page or squire carried it behind him (like on this tapestry) or in front of him (1). The tapestry also reflects another fact: that, as a feudal Knight, Jeanne had her own retinue. It is also known, for example, that at a time when Jeanne had been captured by the Burgundians at Compiegne (23 May 1430), she owned not less than 12 horses.

By the way, she seemed to have liked black horses most which she frequently used in combat, although the last one, on which she fought on 23 May 1430 when she was captured, was gray (“lyart”), and the one on which she entered Orleans (29 April 1429) was white.

A soldier by vocation

The cartoon from Paris showing Jeanne is not her portrait of course but a sketch, which clearly points to the two main features which were striking in the eyes of her contemporaries: her femininity and her belligerence.

Kelly DeVries, an American military historian specializing in medieval military, is the author of one of the few works about Joan of Arc from the point of view of military affairs (“Joan of Arc. A Military Leader“, Sutton Publishing, 1999). His conclusion is unambiguous:

“Joan of Arc was a soldier, plain and simple”

DeVries reflects on the reasons why Jeanne has become such a celebrated historical character. Certainly she failed to end the Hundred Years War. DeVries is of the opinion that both the bias of her trial and the way of her execution may have contributed to this phenomenon. However, “other individuals, men and women, were tried and burned for supposed heresy, and not honored with sainthood, let alone with the number of statues, pieces of artwork, literature, and legends awarded to the Maid’s memory.”

Add to this that a number of other famous saints of that period also do not match Jeanne d’Arc in terms of popularity. Thus, where does the phenomenon of Joan of Arc come from?

DeVries gives his own, comprehensive answer to this question:

“Joan’s renown is attached to her military ability, to the skill she had in leading men into battle against great odds and possible death. This made the greatest influence on her time. For, not long after her death, French military leaders, some she had fought with, and some not recorded as ever participating in her engagements, began to adopt similar tactics to those that she had employed. Her policy of direct engagement/frontal assault was a costly method of winning military contests. But, in the long run, it was more effective in wresting France from the English than any other tactic. As other French generals started to use it, they, too, began to be victorious. Even before Joan died, La Hire captured, by direct assault, the important English-held fortification of Château Gaillard. La Hire performed this tactic well, as did Ponton de Xantrailles, Arthur de Richemont, and the Bastard of Orléans.” (p. 187-188)

Certainly we can add here, that the religious factor was a huge inspiration, both to Jeanne herself and to her followers. But the fame alone of her divine inspiration was not able to convince everyone. The French were divided in their attitude to her. The Chronicles of the time are equally positive and negative in relation to her. Moreover, even among her followers the religious factor would not have played any major role if Jeanne suffered defeats. Her victories in campaigns at Orleans and Patay cemented her position.

Jeanne owed her fame to her early victories – but also to the propaganda about her as the “Holy Maid” who came from God. This kind of fame is, however, incredibly treacherous as Jeanne was to find out herself. On the one hand such fame gives the leader massive support – and fast! – and he can, through enthusiasm generated by himself, contribute to fervor and zeal in his followers performing the tasks assigned by the leader. However, on the other hand, it is enough for such a leader to slip somewhere, to fail to take another city, to fail to win in the next battle or to order a retreat – and doubt about his mission would spread with the speed of a pest.

A leader who does not use any credit created by early enthusiasm generated by propaganda does not have such great support and he has to build up his reputation for a much longer period of time. But a failure may not necessarily lead to his downfall. His strengths and his weaknesses are evaluated in a much more sober way.

Right from the outset of her career Jeanne had enemies who were turning against her at the earliest opportunity. With time passing, they gained the upper hand in the court of Charles VII. By the time Jeanne failed to take Paris without a complete siege, their position had been established to the extent that they succeeded in directing Jeanne to other less important campaigns, which was kind of “sidelining” her, and in which she was told to perform similar tasks as before though on a small scale and without sound equipment – just as if they wanted to lead her to her downfall.

The military career of Joan lasted one year. The second half of that year did not see any brilliant victories with the speed of a “Blitzkrieg”. At times her entire army had no more than a few hundred soldiers. She had, however, a small “war budget” assigned to her by the King. If Jeanne had abandoned her fight at that point, it would have resulted in her total downfall, and even her past successes would not have been sufficient to make her a Saint of the Canon.

We will supplement the above-quoted account by Kelly DeVries by stating that in the end the strength of Jeanne’s personal character helped her survive the period of the worst crisis of confidence and win quite a few victories even if those victories were no longer as dazzling as previous ones had been.But it is precisely the latter phase of her activity which – in our personal opinion – constituted even better proof of the strength of Jeanne’s character and her triumph of will than the early one.

Physical preparation

In order to be able to lead campaigns of war and inspire followers, one needs to have talent, even if limited. And to endure the hardships of these campaigns, one needs to be solidly prepared both in terms of fitness and dexterity.

And here we come gradually to the aforementioned point, where we stated that the appearance of Joan also had something to do with her skills.

It is worth recalling here those testimonies we previously quoted: “each of her limbs was strong” or ” with good proportions of the body and strong”, or “she has incredible strength and resistance to fatigue and wearing armor that she can hold out for six days and nights without removing even one part of the armor.” What else do these accounts confirm if not a solid physical preparedness? Strong muscles and huge physical endurance are not gained, after all, through long prayers in a church and by listening to the sounds of bells while simultaneously inhaling the smell of incense – even if it’s true that these religious elements are able to help a person with spiritually-minded leanings. Religious factors in the life of Jeanne will be discussed in a separate section of this series (Part 6 of this series).

A lot has been said about Jeanne’s skills in the past. Marguerite de la Touroulde (widow of René de Bouligny, the Royal Adviser) expressed the following view about Jeanne during the rehabilitation trial:

“She rode a horse and dealt with a lance like a more experienced soldier and soldiers were amazed.”

But it has been noted elsewhere that she exercised in the military craft. During the same trial another witness, Duke Jean d’Alencon testified on 3 May 1456 that he had seen Jeanne during such exercises soon after her arrival at Chinon where she met Charles VII:

“After the meal the king went for a walk in the near and Jeanne ran up with the spear; the witness, seeing how she carried herself in holding the spear and running with the spear, gave her a horse”

(“Après le repas le roi alla se promener dans le prés, et Jeanne y courut avec la lance; le témoin, voyant comme elle se comportait en tenant la lance et en courant avec la lance, lui donna un cheval”)

During her stay in Nancy with Duke Charles II of Lorraine, Jeanne had confirmed that she could use a lance:

“The Duke (because his were the former stables, where Guyenne-Deschaux is today), gave her a full suit of armor and horse and armed her. She was agile. And they brought a horse and some of the best, saddled and bridled; in the presence of all she jumped on the saddle without sticking her feet in stirrup. A lance was given to her; she rode onto the courtyard of the Castle. She moved. Never armed men handled a lance better. The whole assembled were amazed. The Duke was informed. She was well known for her virtues. The Duke said to Messire Robert: ‘Bring her in; God is going to fulfill his desires’ ” (” Chronique de Lorraine “, 1475) (2)

The “Messire Robert” mentioned in the text was none other than the Castellan of Vaucouleurs, Robert de Baudricourt, the same who had already known the Jeanne’s family, and who organized her journey to meet with King Charles VII at Chinon, and the same one who a few years later also met with Jeanne des Armoises, the “other Joan of Arc” …

What the Chronicle describes is nothing other than a tournament. There were a variety of tournaments and competitions. We do not know, because the Chronicle does not say explicitly which kind was the one depicted above. However, there is no mention that Jeanne entered the “lists” (i.e. a kind of “running track” on both sides of a fence that separates the Knights charging with lances) against any rival. Most likely, therefore, the competition was not the toughest and most dangerous “tournament”, which we associate the term with. This one, in which she took part, was probably lighter, but also requiring equestrian skills, so she was probably either targeting a rotary shield or a “quintaine” (a leather mannequin effigy). The more dangerous tournaments (sometimes called “béhourd”) still take place in our time. And by this we do not mean those fancy shows with replicas of the Medieval armor as attractions for tourists, because in them there is no real fight. What we mean is called “Full Metal Jousting” or tournaments in modified suits of armor. How do they look and what real combat is in them, the Reader can see here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48BS6mM8vd4

This gives you some idea of what tournaments were also like in the past.

Narrow specialization

At the end of his testimony in the rehabilitation trial, Duke Jean d’Alençon offered the following unambiguous conclusion:

“In everything she did, except for issues relating to the army, she was a very simple young girl; but militarily, like handling a lance, assembling the army, directing military operations, directing artillery – she was most skillful. Everyone was amazed that she could act so cleverly and sensibly in the conduct of the war, as if she was a captain of twenty or thirty years of experience, and especially in making use of artillery at which she was most skilled.”

The Knight Thibauld d’Armagnac (“Sire de Termes”) remains consistent with Duke d’Alencon, formulating almost an identical opinion (May 7, 1456):

“Apart from the affairs of war she was simple and innocent; However, in conducting and disposition of troops and in the actual warfare, in command in battle and in stimulating the soldiers, she acted as the most efficient captain in the world, who throughout life was trained in the art of war “.

What is striking in these testimonies is the fact that, in comparison to any other area of life, military affairs were what Jeanne knew best. The above testimony could also suggest that Jeanne was acting both as a Commander in a strictly “technical” way as well as the “commisaire politique” responsible for morale and cohesion of the armed forces assigned to her.

And here things start to become really interesting: someone who excels at something, is, as a rule, not “simple and innocent”, though such may indeed be the impression. It happens more often than not that a person really fascinated by some field and devoting his (or her) entire energy to it, who has at the same time really outstanding intelligence, becomes a kind of a specialist in this field, as he is studying carefully every aspect of it, while about other fields he knows less. Quite often the impression of “innocence” is being made by a person who, being prominent in some area, is celibate. Such a person is often believed “not to know about life”, to be “innocent” etc. Because the area in which he is an expert is “his whole life.”

Against the idea of the total simplicity of Joan speaks (along with many other proofs, mentioned on other occasions) a peculiar rite that Jeanne invented herself (if you believe the source), and in which she involved the Court of King Charles VII, having placed herself as a kind of “priestess” in it:

„One day, the Maid asked the king to give her a present. This request was immediately approved. Jeanne asked for nothing less than the Kingdom of France. The King agreed upon certain hesitation. Jeanne accepted and made four secretaries of the king write it down and the charter was given a solemn reading. The king was a bit stunned, and Jeanne, by showing him to the audience, stated: “This is the poorest knight of the realm!”. Almost at the same time, in the presence of the same notaries, she gave to Almighty God the kingdom of France she had received as a gift. Then, after a moment, obeying an order from God, she invests King Charles with the kingdom of France, and all that she did was written in a solemn act”. (Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Ayroles. “La vraie Jeanne d’Arc” volumes I-IV, 1890-1902, v. I, p. 57-58, on the basis of the “Collectarium Historiarum”, 1429, by the theologian Jean DuPuy in the “Breviarium Historiale” in Poitiers, 1479, by Jean Bouyer)

http://archive.org/stream/lavraiejeanneda03ayrogoog#page/n107/mode/2up

Dominican monk and theologian Jean DuPuy was not in France at that time, but in Rome in the service of the Pope. Therefore he could have at most heard this story somewhere. By the way, if the story is true, one would give a lot to see these documents written by those “notaries”, through which Charles VII gave Jeanne the Kingdom of France and then received it back. One thing seems certain: DuPuy expressed himself enthusiastically about Jeanne, so if it is also true that he was an Inquisitor, he was one of the very few Inquisitors enthusiastic about Joan of Arc.

Duke Jean d’Alençon expressed himself (3 may 1456) more sparingly about the event:

“Then Joan made several requests to the King, among other things, that he offered his Kingdom to the King of the heavens, as the King of the heavens after the offering would do to him, as He had done to his predecessors and to restore his rights to him.”

The child of her era

When talking about warfare, there’s no way not to mention customs prevailing in the 15th century. The rules were quite different. Usually captured aristocrat would not be killed, but kept in captivity (in good conditions) and he could buy his freedom back. Simple soldiers generally did not have such luck and many of them were killed at the hands of those who captured them. Civilians were also killed in war (the townspeople, peasants), but they were generally not a target of massacres. That was in crass contrast to World War II, when soldiers were sometimes treated well or at least tolerably, while at the same time civilians were unscrupulously murdered in bombardments of the great agglomerations.

Military garrisons in the Hundred Years War, stationed in cities, behaved in various ways: in general, the English behaved usually better than the French soldiers of Charles VII, also those led by Jeanne d’Arc – besides, many cities had no English garrisons due to the thinness of English military forces. Therefore, some cities submitted to Charles VII under the condition that Jeanne would not bring her army into them. The worst was feared. And for a good reason: the victorious French, having captured Jargeau, plundered even the church there.

That, at Orleans or Jargeau, Jeanne bellicosely demanded from the English:

“Surrender this place to the King of the heavens and to the noble King Charles, and you will be able to go, otherwise we’re going to slaughter you!”

was really nothing special. After all, to force obedience on the enemy in war, you need to frighten him. That, however, massacres were indeed sometimes taking place – like at Jargeau – there is no doubt. At Jargeau the French unceremoniously slaughtered most of the approximately 700 prisoners; only about 50 remained alive. It is true that the authors of the chronicles do not mention Jeanne as being present during this mass slaughter, which may suggest that perhaps she was elsewhere (but where? Was it so common for a feudal knight, after having captured a village, to leave it to his soldiers and be somewhere else in order not to see what the military were about to do?). But it would be hard to believe that she was not getting to know about such things. And the majority of simple soldiers were killed mainly because in the eyes of their captors they were simply not worth taking because it would be difficult to obtain any ransom for them.

However, let’s take a look at a singular accident described in a testimony during the rehabilitation trial – an example from the time when witnesses tried to testify about Jeanne as positively as possible. Jeanne’s page Louis de Coutes gives us an interesting example of Jeanne’s reaction at the end of the battle of Patay (18 June 1429):

“Jeanne, who was very humane, had great compassion during the carnage. Seeing a Frenchman who had the task to convoy certain English prisoners hit one of them in the head so that he was dying on the ground, she got down from her horse, had him confess, personally supporting his head and comforting him as she could.”

In the testimony by Louis de Coutes there is however no mention of any reprimand given by Jeanne to the Frenchman, who had just murdered a prisoner …

What shows itself here, is the almost “encoded” attitude to the matters of war, in which you could show mercy to the enemy being killed, while at the same time the reason of having him killed went usually unquestioned.

As for Jeanne herself, she used to “mourn” those killed in battle and tried to help the wounded, regardless of whether they were her soldiers or Burgundians or the English.

Those were the days when application of patterns of our today’s law and morality could cause trouble, even in one’s own “camp” and it happened also to Jeanne. And this is how it happened:

There was a captain fighting on the side of the Burgundians, named Franquet d’Arras. He had fought for the Burgundian dukes since 1416. He was known as a good and brave soldier. Unfortunately he had a whole “baggage” of crimes on his conscience as well. He definitely ran out of luck in the spring of 1430 when Joan of Arc decided to go after him. Along with 300 of his soldiers he was returning to his base after a successful raid on the enemy’s territory. Having gotten to know about his whereabouts in the vicinity, Jeanne, who stayed in Lagny, immediately moved against him with about 400 of her own troops. Franquet defended himself skillfully, but reinforcements from Lagny helped Jeanne in the pogrom. Almost all Franquet’s soldiers fell, and he himself was captured. Jeanne intended (so at least she claimed later in her trial) to exchange him for Jacquet Guillaume, owner of “The Bear Hotel” (“Hotel de l’Ours”) near Porte Baudoyer in Paris, who was a conspirator involved in the conspiracy aimed at a coup in the city and the opening of gates for the troops of Charles VII. Guillaume was however killed. Therefore Jeanne decided to hand Franquet over to the civil authorities in Senlis, who wanted him for his numerous murders. The trial of Franquet took 2 weeks, after which he was beheaded. This incident had aggravated her relations with professional military men and not only among her enemies: here an aristocrat, a brave soldier was beheaded contrary to the chivalric code. Jeanne, who herself was a supporter of the code of chivalry, however, had apparently also another type of morality, closer to our current one.

And the question of the almost “routine” plundering of occupied cities, including those occupied by Jeanne’s troops? In Saint-Pierre-le-Moutier Jeanne prohibited the plunder of the local church. Apparently, however, she did not prohibit the plunder of the rest of the city.

What was then her personal attitude to plunder? Was she in favour of it? In our opinion, she was not. And we rely for our opinion on the fact that there is not even one example of a record that she ever participated in it or that she appropriated anything in this way. Of course, the exception is that she used weapons “inherited” from her defeated enemies, but this is also the rule at present.

“The right of winners” to plunder was the thing that few people then tried to erase from the military code of conduct. This was part of conduct of war then.

Attempts at negotiation and aptitude for them

Although Jeanne’s main occupation was the conduct of military operations, she intended to negotiate as well, although in her own warlike manner.

On 12 March 1431, in the afternoon, Jeanne, already tried in Rouen, was asked:

“When asked how she would have delivered the Duke of Orleans, responds that she should have taken enough of the English prisoners in France to have exchanged for him; If she had not taken enough in France, she would have crossed the sea, to find him, by force, in England.

When questioned whether Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret told her unconditionally and absolutely that she would take enough Englishmen to reclaim the Duke of Orleans, who is in England, or that otherwise would cross the sea to find him, responds that yes and that she said so to her King to let her take care of the English lords, who were then prisoners. She further stated that, if she had continued for three years without obstacles, she should have liberated him. To do this, she needed less than three years and more than a year. “ (p. 81 – 82)

If on the one hand the propaganda applied by Jeanne was sometimes bringing excellent results, and her personal example was in a positive sense “contagious”, then, on the other hand, on the field of diplomacy, her efforts ended in a hopeless failure. As an example illustrating this we quote – in footnote (3) her letter to the Burgundian Duke Philip The Good. As a matter of fact, this diplomacy was limited to threats and attempts to convince Philip The Good that no matter what he would have done, he would “never win”. Probably this was also why Philip never responded to that letter, as he also did not respond to her earlier correspondence. He treated them all probably as a list of personal insults. How was he, for example, to react to Jeanne’s “advice” that “if he must necessarily make war, let him go against Saracens”?

This does not mean, of course, that Jeanne wrote “the worst” letters exchanged by the “powerful” during the Hundred Years ‘ War. Her letter is easily comparable with the letter by the then Regent of England, Duke of Bedford, to Charles VII, King of France.

Bedford’s letter is undoubtedly much more impertinent, but let us not forget that such was his intention. Bedford did not try any “démarche” in regard to Charles and the whole letter he fathered only to include all the insults, hostility and contempt to the person who was his direct competitor in the struggle for the French throne. While the task which Joan set for herself in regard to Philip The Good was quite different: to persuade the Duke to switch sides in the conflict.

If Jeanne ever managed to draw anyone to her side, it happened only through her enthusiasm, charm and religious propaganda, and also, in military matters, through threat of the use of force. However, none of her letters betrays any skill of diplomacy or negotiation on her part.

Vitality, courage and shrewdness

Thibauld d’Armagnac in his testimony gives us a glimpse of Joan’s courage:

“After the arrival (at Orléans – MM) the witness saw (her) in the attacks on the bastions of Saint Loup and the Augustins, Saint-Jean-le-Blanc, and on the Bridge, in those attacks, Jeanne was so brave and behaved in such a way that it would not be possible for any man to behave better during a war. Captains and all the others admired her courage and her resistance to pain and fatigue”.

Jean d’Aulon, who accompanied Jeanne as her squire and performed a number of other functions, and was both her quartermaster and bodyguard and who often carried her banner, wrote many years later his extensive testimony for the purpose of the trial of rehabilitation. This is the only testimony written in French for the purposes of that trial. Inter alia he described an incident which had already been variously interpreted by historians and others who had written about Jeanne d’Arc. The incident took place in the beginning of November of the year 1429 during the brief siege of the fortified town of Saint-Pierre-le-Moutier. We include the full section of the testimony relating to that incident in the footnote (4). As the first assault on the town failed, as the town had more troops than expected, and as Jeanne at that time – as has already been mentioned above – had purposely only a small force assigned to her, she had to think of another way to force the defenders of the town into submission. She neither had much artillery nor numerical superiority over the enemy. And then, when her troops withdrew from the attack, she suddenly remained in place with a few men. Her squire, namely d’Aulon himself, concerned about the situation, wished to encourage her to depart due to the danger for her. But she behaved strangely at that point: despite the fact that she had only a small troop at her disposal, ostentatiously removing her helmet from her head – that is, that “salade”, as on our facial reconstruction – responded by saying, that she had “fifty thousand soldiers” with her and that she was not going to move unless she took the town. After which she ordered all her people to rush to fill the moat with fagots to create a bridge for the next attack. The next attack indeed brought success and the town was taken without serious resistance.

Interpretations of that incident vary wildly: from the version of an “army of Angels”, which Jeanne was supposed to see (Leon Cristiani, “Sainte Jeanne d’Arc”), though d’Aulon did not mention “Angels”, to the interpretation of “hallucinations”, where Jeanne, for a brief moment, lost any contact with the surrounding reality (Edward Lucie-Smith, “Joan of Arc”). The theme of “an army of Angels” has surfaced on occasions, in the literature relating to Joan of Arc, in novels, etc, as in the case of a novel by an American author of French ancestry, Pamela Marcantel (“An Army of Angels. A Novel of Joan of Arc”).

Our own interpretation is much simpler, not reaching out to “mysticism” or “psychiatry”, but I think it is much more sober: Jeanne instantly decided to remain longer at the town walls, to be heard (by the defenders) speaking about “fifty thousand” soldiers, then issued a loud command to fill the moat with wood and fagots that gave the impression that much stronger reinforcements were coming. In this way she effectively made the defenders give up any idea of significant resistance.

However, after months of military campaigns Jeanne nevertheless hardened very much as a soldier. In the past she would not attack any city on a Sunday or other Christian holiday. But after a few months – after only four months, to be exact – she was attacking cities even on a feast-day, for example Paris on September 8, 1429, the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. There were also no longer Holy Masses ordered by her for the army before every major battle, nor mass confessions for soldiers. In addition, if from the beginning she was working with some rough and ruthless types of the military – men like La Hire or Gilles de Rais – then, in the year 1430 there were almost exclusively such types around her. Maybe we are not necessarily dealing here with a situation like “one is known by the company he keeps”, but a certain change in Jeanne had become visible; we are not necessarily arguing that it must have been a change for the worse. Probably more likely than not at that point she already resembled Jeanne des Armoises in this regard from the period of the late 1430 ‘s.

Bravery and courage would not leave her until she was taken prisoner. And it was a very single-sided prowess: she was not using defense. Accordingly historians conclude, on the basis of the tactics used by Jeanne that “staying behind the walls was not her military style” and that “defense was not her way of tactics” (DeVries). Jeanne always strove for attack, personally participating in it. Even in the final stage of her campaign, when she was at Compiegne, surrounded by the Anglo-Burgundian troops, she preferred to fight against them by attacking them. So it was, too, on that day 23 May 1430, when she was leading her troops for the last time:

“She mounted a horse, armed like a man and dressed in doublet of rich golden fabric on her armor. She rode a gray steed, a beautiful and wonderful, and presented herself in armor and manners like a captain of a large army. And in this way, with her banner high and fluttering in the wind and surrounded by noblemen about four hours before noon, she charged from the city “. (Georges Chastelain, “Chronique des ducs de Bourgogne”, 1461–1469 )

We have to admit that it is a very nice description for a chronicler of the opposing party. For a moment let us continue with another chronicler, this time her “own”, French:

“As soon as they left, the enemy has been pushed and forced to flee. The Maid charged strongly against the Burgundian army. Those in the ambush saw their soldiers, who had fallen back in great disorder. Then they revealed their ambush and, having spurred their horses, placed themselves between the bridge to the city and the Maid and her group. And some of them threw themselves in the direction of the Maid in such great numbers, that those of her group had no hope of protecting her. And they said to the Maid: ‘Try to go back to the city or you and we are going to be lost!’ When the Maid heard them say so, she spoke to them angrily: ‘shut up! Their failure depends on you. Think only about striking them a blow!’. Even when she was saying this, her men did not want to believe her and forcibly made her move back to the bridge. And when the Burgundians and the English saw that she tried to return to the city, with great effort they moved to capture the bridge. And there was a great clash of arms.” (Perceval de Cagny, “Chroniques de Perceval de Cagny”, from 1438 onwards)

The moment of Joan’s capture also had a few descriptions in the French version (5), the Burgundian version (6) and, of course, in the version given by Jeanne d’Arc herself (7). They are, in principle, in agreement with each other when it comes to the attitude of Jeanne, the differences being in the details (Jeanne expressed herself more modestly on this subject). They show that, as Jeanne fought mainly by attacking, so as a result of her attack she was also taken prisoner.

The moment of Joan’s capture also had a few descriptions in the French version (5), the Burgundian version (6) and, of course, in the version given by Jeanne d’Arc herself (7). They are, in principle, in agreement with each other when it comes to the attitude of Jeanne, the differences being in the details (Jeanne expressed herself more modestly on this subject). They show that, as Jeanne fought mainly by attacking, so as a result of her attack she was also taken prisoner.

Joan would most likely not be herself if she did not try to escape from captivity. The first time she did it shortly after she was captured. She was taken to the Castle Beaulieu-Les-Fontaines near Noyon. She was locked in a room in the tower on the right side from the entrance on the first floor. The floor was made of wooden planks. Joan took out a pair of these boards from the floor and made it to the ground floor. There she locked two guards in their room with a key, when the third one caught her.

Noting that attempt, however, we have to analyze a certain fact which is still subject to controversy and which refers to another attempt to escape:

An attempt to commit suicide or attempt to escape?

Officially, a version is sometimes quoted from “Chronique des Cordeliers de Paris”, according to which, being imprisoned in the castle of Beaurevoir, Jeanne tried to “escape through the window, but then what she was lowering herself with, snapped and she fell from the highest floor. She almost smashed her kidneys and back, and was sick for a long time from the wounds.”

However, another version of this story appears in the testimonies of Joan of Arc at Rouen (March 14, 1431):

“First of all, she was asked why she threw herself from the tower of Beaurevoir. She replied that those of Compiegne, to the age of seven years, would be burned and slaughtered and she preferred to die rather than live after such destruction of good people; and it was one of the reasons of her jump; and another was that she knew that she had been sold to the English, and would prefer to die rather than be in the hands of the English, her enemies “. (p. 90)

Therefore, the judges were convinced that she tried to commit suicide, which was considered at the time to be a particularly mortal sin. But let’s take the rest of her testimony:

“When asked if her jump followed the advice of her voice, replied that St. Catherine told her almost every day, not to jump, and God would help those in Compiegne. And Jeanne said to Saint Catherine that since God help those from Compiegne, she wanted to be present at there at that time. And Catherine said, ‘you have to endure it patiently and you will not be released until you will see the King of the English’. And Jeanne replied: ‘verily, I don’t want to see, and I’d rather die than be put in the hands of the English.’

Asked whether she told the Holy Catherine and St. Margaret: ‘ will God allow the good people of Compiegne die so horribly, etc? ‘, replied that she had not said ‘so horribly’, but that she expressed herself in this way:‘How could God allow people from Compiegne, who were and are so loyal to their Lord, die!’ After the fall, for two or three days she did not want to eat. As a result of the fall she so was bruised, that she could not eat or drink; and during all that time she was comforted by Saint Catherine, who ordered her to confess and ask God for forgiveness; and that without doubt those of Compiegne would receive help before St. Martin’s day in winter. Then she started to recover and eat, and soon she recovered.

When asked whether, when she jumped, she intended to kill herself, replied that no, but leaping entrusted herself to God. And she wanted, through the leap, to escape and avoid being handed over to the English.

When asked whether, when she regained speech, she blasphemed and cursed God and His Saints, which is attested by a witness, replied that she did not remember that she ever blasphemed and cursed God and His Saints, whether it be at that place or any other and that she did not confess this, since she retained no memory of what she did or said.

Asked whether she intended to rely on the information already obtained, or to be obtained, said: ‘I rely on God and nobody else and on a good confession.’ “

On the same day in the afternoon, she was asked a cumulative question:

“When she was reminded that she attacked Paris on a Holy Day; that she had a horse that belonged to our Lord, the Bishop of Senlis; that she threw herself from the tower of Beaurevoir; that she wore male dress; that she had sanctioned the death of Franquet d’Arras: did she not think that she had committed a mortal sin?”

Her answer was also cumulative, here we quote only an excerpt relating to her leap from the tower:

„..’.As for my fall from the Tower of Beaurevoir, I have done so not out of desperation, but thinking about saving myself and helping the good people, who were in danger. After the fall I confessed and I asked for forgiveness. God forgave me, not because of anything good in me: I acted wrongly but I know thanks to the revelation from Saint Catherine, that after I confessed, I was forgiven. It was on the advice of Saint Catherine that I confessed’.

When asked whether she has done great penance, she said she has suffered great damage by jumping down. Asked if she believed that the great evil done by her by jumping, was a mortal sin, she replied: ‘ I know not, but I leave it to our Lord. “( “je n’en sais rien, mais m’en attends à Notre Seigneur”)

We are leaving any possible comment and conclusion in this matter to the Readers.

On our part we add that we take into account the various “scenarios”. During the trial in Rouen the matter was not finally clarified. It was not concluded what exactly happened there and how Jeanne ended up unconscious on the ground under the tower. An attempt to commit suicide was attributed to her but the judges were not completely convinced. They used two expressions addressing the incident either as “throwing herself” or as “jumping”. Jeanne herself talked about “throwing herself”, “jumping” and “falling”. Perhaps she was seeking death. Or perhaps she was seeking rescue through escape. But it is possible that she decided to stake everything on a chance, hoping that either she would escape, or, if not, then at least she would die, avoiding falling into the hands of the English. In this sense, her words that she “entrusted herself to God” can even carry some truth, especially since Jeanne lacked neither courage nor inclination to risk.

Final remarks

Joan of Arc seems to us to have been a kind of impetuous person, full of vitality, and completely different from her “images” known to us from iconography. In iconography Jeanne, with her banner and in full armor, has her eyes fixed on the sky. It’s not our intention here to “demote” iconography, but it tries to use symbolism to mold the military mission of Jeanne with a religious mission, thus distorting her personality. In fact, she was a lively person, enterprising and extremely energetic. We have already tried to show this before. Now we are going to add a few final comments to this part.

Our own assumption is that if Jeanne d’Arc appeared among us, some would be more than delighted with her and more inspired by her; many others would be surprised, and still others would shun her, as centuries of legends, iconography, those sometimes ad nauseam monotonous images, and a focus on mysticism that almost smells of incense, has created in the end a distorted image of the French heroine. Compared to such an artificial image, the truth looks less favourable for many and less “perfect”.

A lot of people would be scandalized by the fact that there was more toughness in Jeanne, more belligerence, severity and harshness than they imagine. Their own ideas tend to portray Jeanne as if she was more of a spirit, more “phantom” (“doketos”) rather than a living person of flesh and blood. If Joan of Arc was supposed to be such a character, she would have stood no chance of influencing and electrifying professional soldiers and thugs, as she would be for them far too bland – this is our personal opinion on the subject.

Her belligerence was uncompromising. Her vision of peace in the country could have been, in her opinion, executed only through war. Her attempts at mediation and diplomacy give her opponent only one alternative: “surrender, or we will destroy you!” Her piety was mixed with idealism and fanaticism.

Her belligerence was uncompromising. Her vision of peace in the country could have been, in her opinion, executed only through war. Her attempts at mediation and diplomacy give her opponent only one alternative: “surrender, or we will destroy you!” Her piety was mixed with idealism and fanaticism.

However, in order to be able to understand this person, we must first learn to understand her times, her medieval type of religiosity. We need to know what the Hundred Years’ War was, how it was conducted, what was then the norm. And it is the more necessary when we consider the issue of holiness. And here it shows itself fully that when the “official” image of Joan of Arc was created, the cart was put before the horse, so to speak. The holy image was created like a shimmering figurine of Meissen porcelain, without proper explanation of her era. When this “porcelain figurine” is set against the background of the existing records of her era, it loses its splendour. Citing of any facts is interpreted almost as “vilification”. I recall that when I published a couple of texts about Jeanne in the blogosphere of the Polish magazine “Fronda”, one of the more Orthodox portal users asked me in a comment under the text what Joan of Arc had done to me since again (!) I smeared her memory. Because the question was asked without any aggressive tone, so I too politely asked the user in which way, specifically, in his opinion, I had “smeared” her. I have not received an answer, even though I have guessed what he probably meant. Precisely this gap between historical records and their selective treatment for religious (and political) expediency causes the quotation of facts alone to be interpreted as an attack, as an insult, almost as sacrilege.

Therefore, in the following sections we will concentrate more on this historical background, to try to better understand it.

Universally accepted is the notion that Jeanne considered her task to be the preparation for the coronation of Charles VII, and a victory over the English. However, there was at least one moment during her campaign two months before its end in which she was pondering over possibly taking her fight in a different direction. In March 1430, her famous “letter to the Hussites” was written in which she heralds the possibility of moving against them. This letter was signed on her behalf by her confessor, father Jean Pasquerel, who was also most likely its author. It differs completely in style from any of Jeanne’s other letters. But surely its contents had been approved by her.(8)

This episode could suggest that after months of being “sidelined” and seeing her efforts sabotaged by even those in whose interest those efforts were taken, she could have looked for another target for her belligerence and religiosity. But it could have also been an occasional incident where she never intended to fulfill her threat.

So, as the individual historical sources (and their various interpretations) sketch different images of the heroine, so various are and will be assessments of her. The gap between these assessments at their extremes run between two poles, from “Someone is bent on slandering Joan!” to “Is it all true? In that case, what kind of a ‘saint’ was she?”

In our own “painstaking search for Joan” we are not looking for so-called “clear” answers and we take a variety of versions into account, without siding in advance with the “official” or the “alternative” one because we are interested in Joan of Arc herself, and not in any instrument of propaganda, whether it be Catholic or anti-Catholic, religious or political. We understand, though, that this character is suitable for propaganda. We like the statement made by the military historian Kelly DeVries: “we should not denigrate that legacy; instead we should study it”.

As an interesting detail, let us just note the often surfacing reference to… Jeanne’s appetite. The so-called “letter” by Perceval de Boulainvilliers, already quoted by us, mentions that “she eats little, limits herself in drinking wine”.

During the storming of the Tourelles in Orléans, Jeanne was wounded by an arrow from a crossbow. After the fight, as Jean de Dunois, the “Batard d’Orleans”, testified:

“Jeanne was taken to her house, to receive the care which her wound required. When the surgeon had dressed it, she began to eat, contenting herself with four or five slices of bread dipped in wine mixed with a large quantity of water, without, on that day, having eaten or drunk anything else.”

Testimonies such as these quoted here make some authors inclined to believe that Joan of Arc suffered from anorexia (anorexia nervosa). In our opinion this is a completely misconceived conclusion. Anorexia causes the slow emaciation of the body what was not true in Joan’s case despite her tireless activity. Jeanne was probably pious enough to fast regularly on Fridays, by eating a few slices of bread dipped in wine. While wounded, she could just as well fast, promising herself in this way a speedier recovery. Was it customary for her to “eat little”? It probably depends: compared to whom… The attached Link leads to an article showing that the “list of illnesses” attributed to Jeanne is much longer (including epilepsy). Of course, we are not against considering a variety of such possibilities. We ourselves also do not exclude certain versions of the life of Joan of Arc which are not accepted by the “Orthodoxy”. We are, however, of the opinion that one needs more evidence to draw conclusions. It looks however, like the experts of Jeanne’s health are pronouncing their diagnoses completely in the dark. In these circumstances it is probably a sort of a “miracle” that on their list of diseases they did not place progeria or hydrocephalus…!

And – just to end this part on a humorous note: The vehemence of Jeanne could be a warning to unwary men. When she was already imprisoned in Rouen, she had to get a feminine dress (so far she was wearing male attire). Visiting Rouen was the Duchess Anna of Burgundy (1404 -1432), sister of Philip The Good and wife of the English Regent Bedford. She ordered a dress for Jeanne and entrusted the task to the tailor from Rouen named Jeannotin Simon. When taking measurements, Jeannotin touched the breasts of Joan by chance. She pushed him back violently, then violently boxed his ears. She did it also a bit earlier in the Beaurevoir castle to Raymond (Haymond) de Macy, but he reportedly tried this “trick” for fun, so he probably deserved the “treatment”…

FOOTNOTES

(1) When Jeanne’s banner was carried in front of her during her triumphant entry to Orléans, it brought attention to yet another, seemingly small, skill she possessed. The manuscript known as “Le journal du siege d’Orleans” (“Diary of the siege of Orléans”) recorded under date of 29 April 1429 as follows:

“And there was wonderful pressure of the crowd to touch her or the horse on which she rode, so great, that one of those carrying torches came close to her banner, so that it caught fire. At that time she spurred her horse and gently turned it towards the banner to be able to put down the fire, as if she was long in wars. And the soldiers wondered, and the townspeople of Orleans”.

(2) The “Chronicle of Lorraine” is sometimes treated as of little value. However, the information about Jeanne’s tournament at Nancy is basically in line with the testimonies cited earlier, testimony of Marguerite de la Touroulde and Jean d’Alencon. The only two items we do not believe are the assertions that “never” armed men were more skilled in the use of lance than Jeanne and that Jeanne was able to mount a horse without putting her foot in a stirrup. Knights in full armor were not able to just jump onto a saddle, because they were carrying 16 – 20 kilograms of gear. Later the King of England Henry VIII had to be seated on a horse with the help of a crane…

There could de facto be more shows like the one in Nancy in the first half of February 1429 (according to the old calendar it was the year 1428, since the new year was calculated from Easter Sunday). Marguerite de la Touroulde in fact attests to Joan’s skills, but, as she claimed during the trial of rehabilitation (April 15, 1456) – she did not meet Jeanne earlier than after the coronation of the King in Reims (17 July 1429), i.e. after more than five months since the show at Nancy. She also did not accompany Jeanne during her military campaign.

Jeanne received a gift from Duke Charles II of Lorraine of 4 francs and a horse – a probably his own black horse which he could no longer ride himself for reasons of poor health (he died two years later). It is likely, therefore, that it was the tournament which became the reason for the gift. It was not the only horse which she received at the beginning of her military activities – and in fact even before. Another was the horse from Jean de Metz which was purchased by him for “approximately 16 Franks” (that is, it was a “common” horse; a good military one would cost from a few dozen to more than two hundred Francs). That could mean that the word “running with a lance” reported later in Chinon by Prince d’Alencon was also a horseback riding – depends on how to interpret the phrase “courir avec la lance”. Because having already two horses, Jeanne would not need to run on her own legs … And d’Alencon himself, as we read, offered her another horse just after her exercises with a lance. Which means that even before her military mission Jeanne had already owned three horses, of which at least two after having demonstrated her skills.

(3) ” + Jhesus Maria

Great and formidable Prince, Duke of Burgundy, Jeanne the Maid requests of you, in the name of the King of Heaven, my rightful and sovereign Lord, that the King of France and yourself should make a good firm lasting peace. Fully pardon each other willingly, as faithful Christians should do; and if it should please you to make war, then go against the Saracens. Prince of Burgundy, I pray, beg, and request as humbly as I can that you wage war no longer in the holy kingdom of France, and order your people who are in any towns and fortresses of the holy kingdom to withdraw promptly and without delay. And as for the noble King of France, he is ready to make peace with you, saving his honor; if you’re not opposed. And I tell you, in the name of the King of Heaven, my rightful and sovereign Lord, for your well-being and your honor and [which I affirm] upon your lives, that you will never win a battle against the loyal French, and that all those who have been waging war in the holy kingdom of France have been fighting against King Jesus, King of Heaven and of all the world, my rightful and sovereign Lord. And I beg and request of you with clasped hands to not fight any battles nor wage war against us – neither yourself, your troops nor subjects; and know beyond a doubt that despite whatever number [duplicated phrase] of soldiers you bring against us they will never win. And there will be tremendous heartbreak from the great clash and from the blood that will be spilled of those who come against us. And it has been three weeks since I had written to you and sent proper letters via a herald [saying] that you should be at the anointing of the King, which this day, Sunday, the seventeenth day of this current month of July, is taking place in the city of Rheims – to which I have not received any reply. Nor have I ever heard any word from this herald since then.

I commend you to God and may He watch over you if it pleases Him, and I pray God that He shall establish a good peace.

Written in the aforementioned place of Rheims on the aforesaid seventeenth day of July”. (Original version)

(4) “That, after the Maid and her followers had made siege against the town for some time, an assault was ordered to be made against the town; and so it was done, and those who were there did their best to take it; but, on account of the great number of people in the town, the great strength thereof and also the great resistance made by those within, the French were compelled and forced to retreat, for the reasons aforesaid ; and at that time, the Deponent was wounded by a shot in the heel, so that without crutches he could neither keep up nor walk: he noticed that the Maid was left accompanied by very few of her own people and others; and the Deponent, fearing that trouble would follow therefrom, mounted a horse, and went immediately to her aid, asking her what she was doing there alone and why she did not retreat like the others. She, after taking her helmet [“salade”] from her head, replied that she was not alone, and that she had yet in her company fifty thousand of her people, and that she would not leave until she had taken the town; And the Deponent said that, at that time whatever she might say-she had not with her more than four or five men, and this he knows most certainly, and many others also, who in like manner saw her; for which cause he told her again that she must leave that place, and retire as the others did. And then she told him to have faggots and hurdles brought to make a bridge over the trenches of the town, in order that they might approach it the better. And as she said these words to him, she cried in a loud voice: “Every one to the faggots and hurdles, to make the bridge!” which was immediately after done and prepared, at which the Deponent did much marvel, for immediately the town was taken by assault, without very great resistance;“

There were famous stratagems in history by which enemies were fooled. Hannibal, before the battle against the army of the King of Pergamum, Eumenes II, sent a letter to him by a messenger only and exclusively in order to locate his ship, on which he then concentrated his attack. In March 1271 the famous Islamic leader and Sultan Baibars, using a fabricated letter from the Grand Master of the Hospitallers (later Maltese Order) of Tripoli “allowing” the crew of the strong fortress of Krak des Chevaliers in Syria to surrender. In March 1942, HMS “Campbelltown” used the German flags to confuse the enemy during operation “Chariot” in Saint Nazaire, and SS-Standartenführer (i.e. colonel) Otto Skorzeny, during the offensive in the Ardennes (December 1944), used English-speaking Waffen-SS-Men in American uniforms behind the lines of the American troops.

Jeanne cleverly decided to use the simplest of such stratagems.

(5) “The captain of the place, seeing the multitude of Burgundians and the English ready to enter the bridge and fearing the loss of the city, ordered to lift the bridge and close the gate. And so the Maid remained outside and a few men along with her. When the enemies saw it, they all rushed to capture her. She resisted them very hard and in the end she had to be capture by five or six men at a time, one seizing her, the other her horse, and each of them saying ‘surrender to me and give me your promise ‘ (a promise that one won’t run away – MM.). She replied: ‘I will give my promise to someone else than you and I will offer him the oath ‘. And while saying other similar things she was taken out to the tent of John of Luxembourg “ (” Chroniques de Perceval de Cagny ” )

(6) “Then the Burgundians repulsed the French to their camp and the French, along with the Maid, began to withdraw very slowly, because they failed to gain the advantage over them, and found only danger and loss in them. Upon seeing this the Burgundians, covered with blood and not being content with just pushing them into defense, as they could not damage them more than by pressing firmly on them, they assaulted them boldly, so on foot and on horseback, and they did great damage to the French. Then the Maid, rising up over the nature of women, gained great power and made a great effort to protect her unit from defeat, remaining behind as commander and as the bravest of soldiers. However, fortune allowed the end of her glory and that she carried a weapon for the last time. A bowman, a raw and bitter man, full of anger, that a woman of whom so much was said that she was able to defeat so many brave men, as she did, grabbed her by the edge of her wappenrock of golden fabric and threw her off her horse flat on the ground. She was not able to find escape or get help from her soldiers, even though they tried to help her get back on her horse. But an armed man called ‘Le Bâtard de Wandomme’, who arrived just when she fell, so pushed towards her that she gave him her promise because he said he was a noble”. (“Chronique des ducs de Bourgogne”)

(7) “She passed through the bridge and the French rampart and moved with a company of soldiers of her party against the troops of the count of Luxembourg, whom she had repulsed twice to the Burgundian camp and the third time to the middle of the road. And then the English, who were there, cut her and her men off, between them and the rampart. While retreating in the field towards Picardy, near the rampart, she was captured. Between Compiegne and the place where she was captured, there is nothing but the stream and rampart with its ditch.” (trial in Rouen, Saturday 10 March 1431) (p. 73)

(8) “Jhesus – Maria